Information Literacy Perceptions Survey Results

Survey of almost 100 librarians at academic libraries finds a strong believe in the importance of information literacy.

Summary

Over the last 2 decades, academic libraries have experienced dramatic transformations. The need for some services that were once essential to academic research like Interlibrary Loan and providing local access to printed journals have diminished importance. At the same time, a number of other services have gained an increased prominence. This survey explores perceptions around one of those services with increased prominence: Information Literacy instruction.

Background—The Value of a Local Copy

Throughout the 20th century, the value of a local copy was high. If you wanted to read a book, or an article in a scholarly publication you needed to get your hands on a printed copy. If you wanted a sound or video recording, a map, or an image, you needed a local copy. If not on paper, then on a cassette, or a disc in whichever of the succession of evolving storage formats was then current.

Libraries, in those years, existed to provide access to a local copy. Librarians, catalogued and preserved the local collection and harnessed the arcane mysteries of the interlibrary loan system when needs went beyond the local collection. They also served as curators, navigators, and guides, listening carefully to local needs and matching them to the collection. They were the experts who knew genres, disciplines, and repositories. They could tell you where the answer to a specific research question likely lay and suggest resources you might not yet have considered.

Somewhere around the turn of the century, a disruption began in the value of a local copy. That was when Google began refining their algorithms for intelligently searching massive data sets. At first, the data was just web pages, but the search experience was unprecedented. People could enter just a few keywords or phrases to get instantaneous and highly relevant results. The experience was so good, that the whole notion of cataloging the web quickly became irrelevant.

A rapid expansion in the type and quality of information available online soon followed. Current news, official documents, primary communication channels, all began to live online and a shrinking percentage of it was ever printed. Herculean efforts like the Google Books project and Google Scholar also began with the goal of digitizing the printed collections of the world’s largest libraries, to also make them available online. The combination of intelligent full-text searching and the sheer scope of online indexed material quickly dwarfed the power of a local collection expert. With so much of the world’s information directly accessible to anyone with an Internet connection, the perceived value of a local copy, and a campus library, and the librarians who staff them, has been impacted.

The central question: What is the value of a local campus library?

The central question behind this survey is this: What is the value of a campus library?

In the last 20 years, many potential answers have emerged. Here’s a sample:

Libraries add value to the larger campus community by:

- Providing inviting spaces for study and small group collaboration.

- Providing discipline-specific research guidance.

- Preserving and archiving physical materials that have historical value, have not yet been digitized, or don’t lend themselves to digitization.

- Managing copyright issues for “course packs,” collections of materials that are organized by faculty to share with students in a specific course context.

- Managing subscriptions to journals, periodicals, and other scholarly publications

- Providing information literacy instruction, thus allowing faculty to focus more on their own disciplines.

These ideas are not mutually exclusive, but It is information literacy that is the focus of this survey’s inquiry. We wanted to understand more about how information literacy is currently valued and perceived.

Survey Results and Analysis

This survey collected responses from just under 100 academic librarians, mostly in the US and Canada, a small sample, statistically speaking, yet still enough to provide some useful insight. Here are the responses to each of the questions.

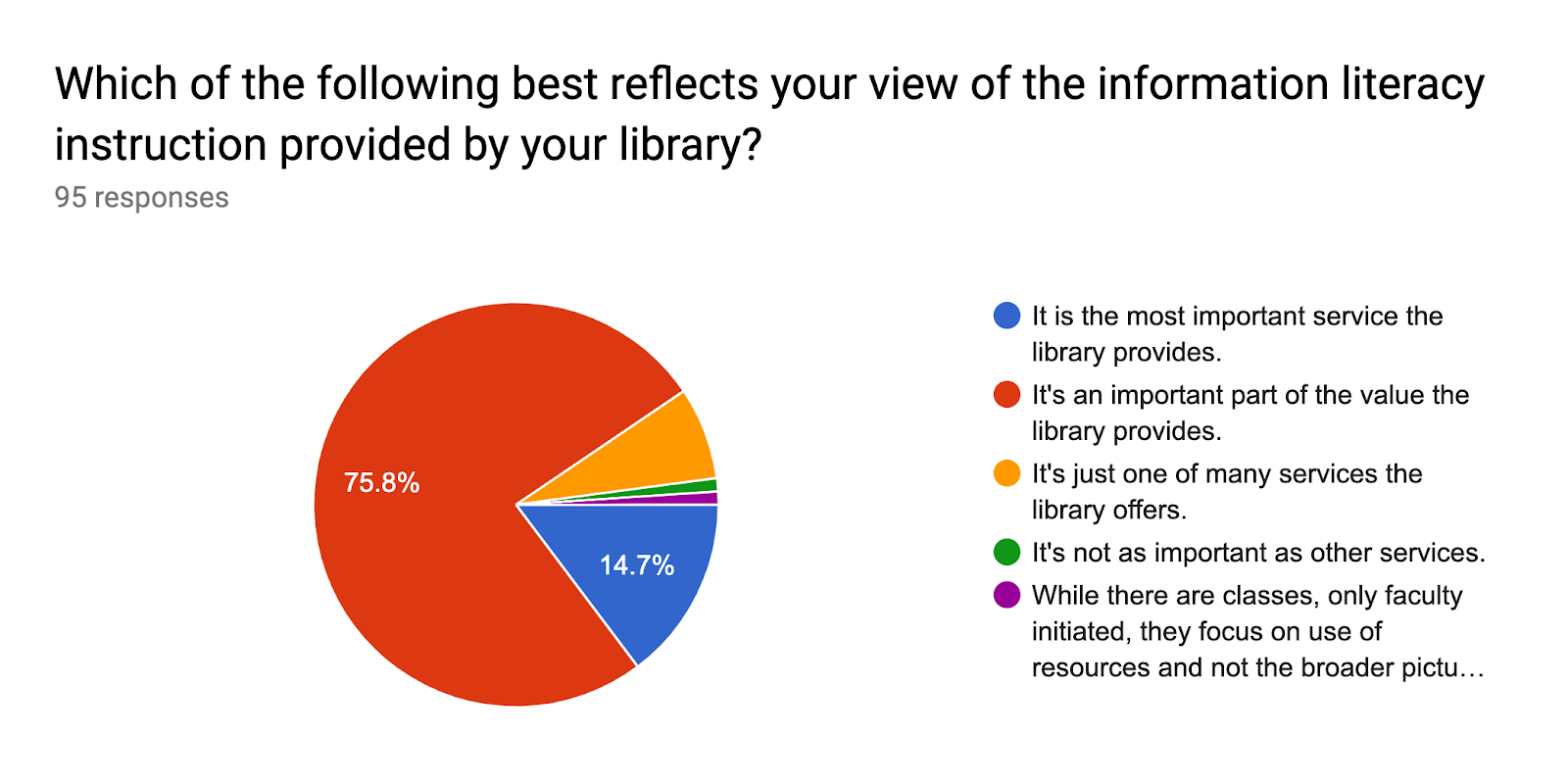

An overwhelming majority (almost 90%) of respondents believe information literacy instruction is important and, intriguingly, almost 15% believe it is the most important service the library provides. 7% felt it was just one of many services and only one respondent felt it was not as important as other services.

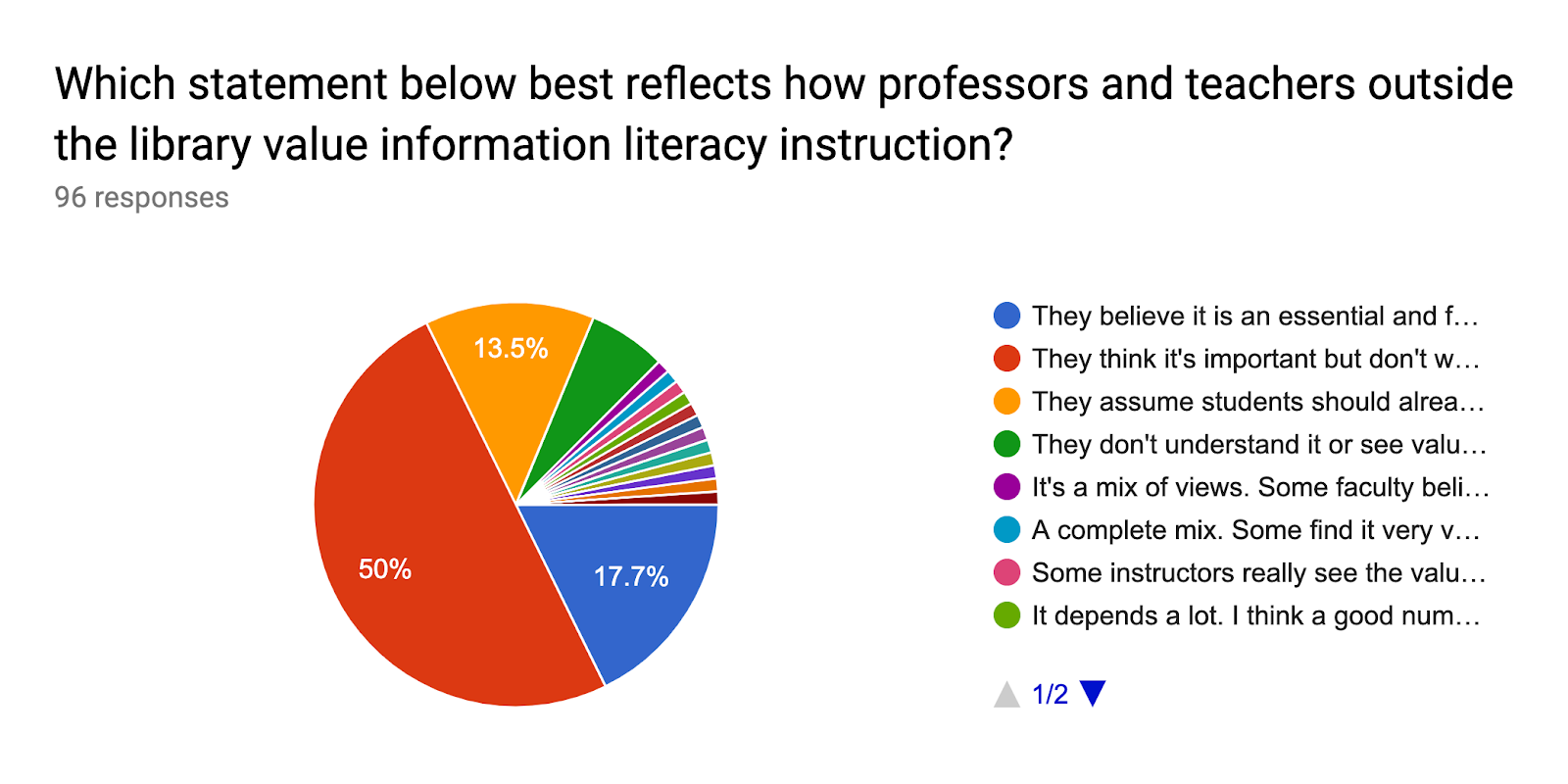

The largest segment of respondents (50%) see professors and teachers putting high value on information literacy, and almost 18% perceiving it to be essential and foundational. 13% of respondents saw faculty assuming students should already understand it without being taught. 14% of respondents found it hard to settle on one view to characterize faculty sentiment toward information literacy. Only 6% believe that general faculty don’t see value in it. There seems to be an overwhelming majority perception that faculty don’t want to spend their own class time focusing on teaching info lit. This may be the single most important factor in why info lit instruction represents an opportunity for the library to provide meaningful value for the larger organization.

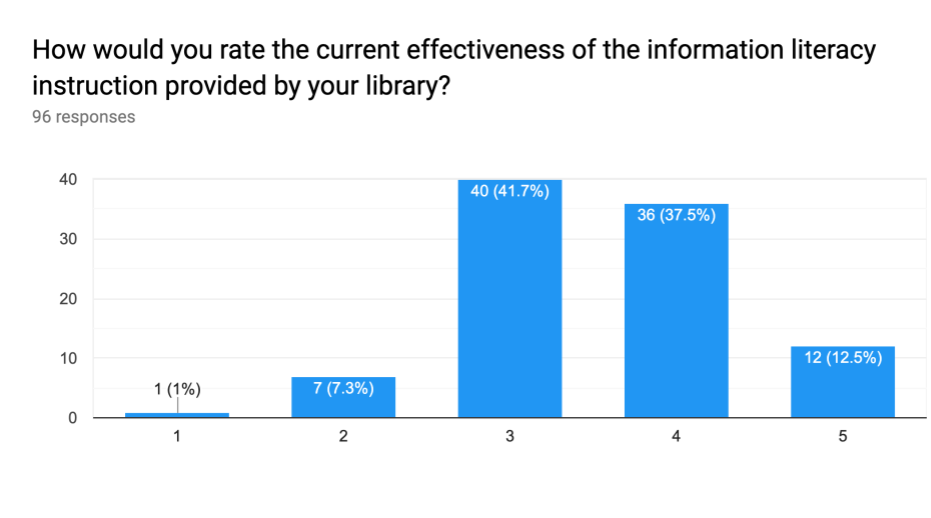

The largest group of respondents (42%) rated their library’s info lit instruction with only average effectiveness. 12% ranked the instruction as “exceptionally effective” and 37% leaned toward effective. This seems to indicate that it would be worth a follow on survey asking how the instruction could be better. By reaching more people? By having a greater impact? There is clear sense that the current instruction is worthwhile but could be better.

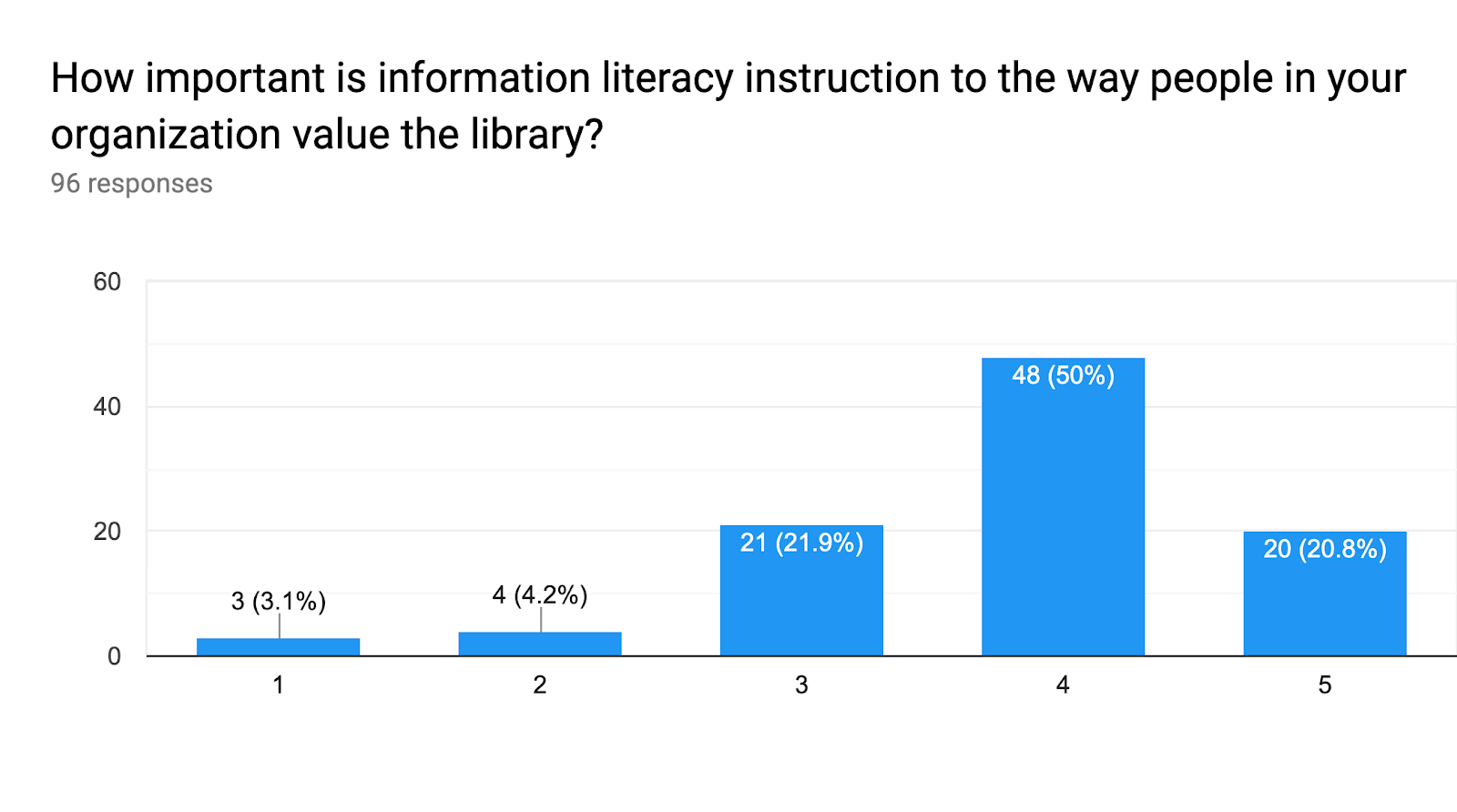

This result triangulates and confirms the finding above about how teachers and professors outside the library see information literacy. 71% tilt toward the high end of the scale, 22% are at the midpoint, and only 7% tilt toward the organization not valuing info lit instruction.

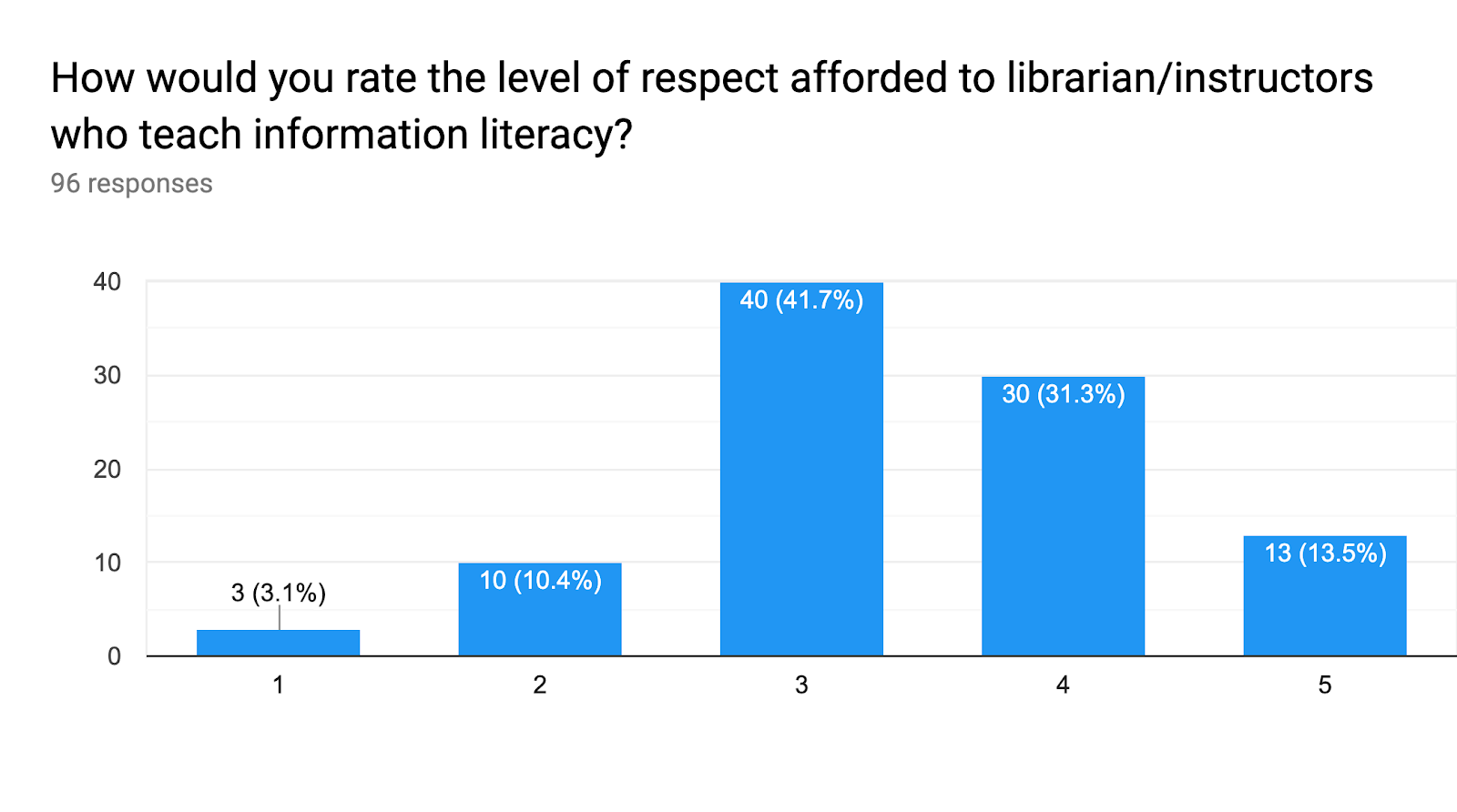

It is interesting that responses to this question almost exactly paralleled the responses to the question about the effectiveness of info lit instruction. There appears to be a correlation between the amount of respect afforded to librarian/instructors and the effectiveness of their instruction though the nature of that connection is not clear. Enough librarians feel highly prized or at least valued for their instruction that it carries on. If this were an election decided by simple plurality, though, we might have to call “meh” the winner.

Which of the following does your library currently use to provide information literacy instruction?

98% Live in person classes

92% One-on-one instruction

58% Asynchronous online instruction

37% Live online instruction

10% Live online classes

In person instruction appears to be the rule for info lit instruction. This fact emphasizes the importance of good librarian instructors. The way this question is phrased, though, doesn’t necessarily indicate that most instruction happens in person as opposed to online, just that almost all libraries offer it in person. It would be worth some follow up research on the percentage of instruction that happens online, particularly as a growing share of college instruction is moving online and there is a growing need to reach remote students.

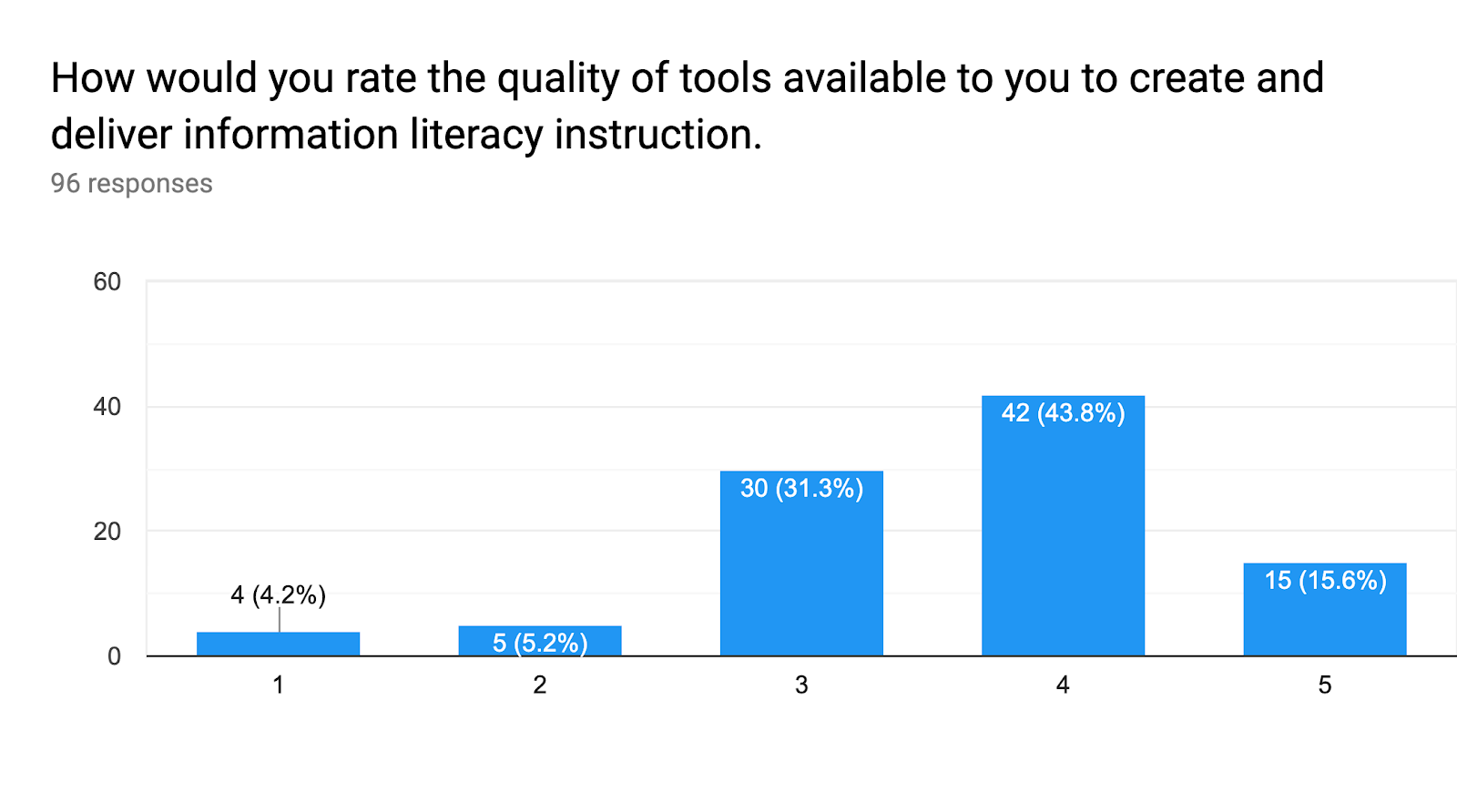

It is encouraging that available tools don’t seem to be a serious hindrance to the delivery of information literacy instruction. There is just enough softness in this response, to think that better tools might be one way to make the instruction more effective, but a majority of respondents seem to feel positively about the tools available to them.

Conclusions

Librarians at academic institutions generally believe that information literacy is very important and they believe that their colleagues throughout the organization share that view, if with slightly less perceived enthusiasm. Librarian instructors appear to have both the will and the means to deliver that instruction, thereby lifting the profile and the perceived value of the library within the larger campus community. There are very likely things that libraries could do to deliver this instruction more effectively and to place more value on the librarian/instructors that deliver this training. It’s likely that these efforts would be fruitful for the status and the perceived value of the library within the larger institution.

About the author: