The Library Education Perceptions Survey

Do librarians believe that an educational focus is the way forward for their library? This survey finds that they do not.

Many thoughtful and well informed people have proposed new visions and ways forward for libraries in the dramatically altered information landscape of the last 20 years. Some of the most influential voices in the library community have suggested that libraries need to become educational institutions, to have a singular education focus, and represent librarians as educators in order to survive. We were curious how much traction this argument has attained. This survey finds that librarians generally have not adopted education as a primary focus. While they see education offerings as important, they don’t see education as the primary mission of their library and don’t believe that’s what the public expects of them.

Background—The Value of a Local Copy

Throughout the 20th century, the value of a local copy was high. If you wanted to read a book, you needed to get your hands on a printed copy. If you wanted any news beyond what the networks were broadcasting over the airwaves at any given moment, you needed a local copy of a printed paper, or a magazine. The same was true for movies and music. If you wanted anything other than what someone else was choosing to broadcast on TV or on the radio at the moment, you needed a local copy—a cassette, or a disc in whichever of the succession of evolving storage formats was then current.

Libraries, in those years, existed to provide access to a local copy. Librarians, catalogued and preserved the local collection. They also served as curators, navigators, and guides to that collection. They listened carefully to local needs and matched them to the collection. They were the experts who knew genres and repositories. They could tell you where the answer to a specific research question likely lay and which book you might really like next.

Somewhere around the turn of the century, a disruption began in the value of a local copy. That was when Google began refining its algorithms for intelligently searching massive data sets. At first, the data was just web pages, but the search experience was unprecedented. People could enter just a few keywords or phrases to get instantaneous and highly relevant results. The experience was so good, that the whole notion of cataloging the web quickly became irrelevant.

A rapid expansion in the type and quality of information available online soon followed. Current news, official documents, primary communication channels, all began to live online and a shrinking percentage of it was ever printed. Herculean efforts like the Google Books project also began, with the goal of digitizing the printed collections of the world’s largest libraries, to also make them available online. With so much of the world’s information directly accessible to anyone with an Internet connection, the perceived value of a local copy, and by extension, a local library, and the librarians who staff them, has come into question.

The central question: What is the value of a local library?

In the last 20 years, many thoughtful proposals have emerged to the question of what value a local library ought to provide. Here’s a sample:

Libraries can add value to a community by:

- Providing Internet access to people who can’t afford it at home (Social Service/Education)

- Expanding access to electronic information that requires a subscription or payment like eBooks, databases, newspapers journals, and magazines (Recreation/Education)

- Providing access to physical books for people who prefer that form factor (Recreation)

- Offering a daytime haven to the homeless (Social Services)

- Supporting new startup businesses with a working space and information support (Social Services)

- Providing meeting spaces and a venue for community events (Recreation)

- Providing early childhood education, particularly for the disadvantaged (Education/Social Services)

- Providing an appealing public space for recreation and relaxation--an indoor public amenity with free wifi (Recreation)

- Supporting public schools with homework help, tutoring, maker spaces, and after-school programs (Education)

- Providing opportunities for adult continuing education, particularly self-directed education for people who can’t afford to go back to school (Education)

As noted above, these answers can be collected into a few broad categories: Education, Recreation, Social Services. Each of these potential answers have strengths and weaknesses.

Libraries that focus on providing value through recreation fit comfortably with a municipal funding source. At the same time, however, they compete for funding with other offerings like ball parks, senior centers, and swimming pools. And because these services are all nice-to-have, rather than essential, they are often the first to get cut when municipal budgets get lean.

Libraries that focus on providing value through social services find it easier to make a case for being essential. It’s relatively difficult, however, to make the case that they are the best delivery vehicle for those services. Funders ask whether day-care subsidies, better homeless shelters, or more social workers, for example, might not meet those needs more effectively. And perhaps more probingly, they ask whether credentialed librarians are absolutely necessary if social services are the goal.

The argument for providing value through education benefits from a close alignment to the function libraries have traditionally performed because libraries have always been about access to information. Rather than just cataloging and preserving a local collection, however, contemporary libraries can help curate an overwhelming world of available information, online or in print, to address local needs. Librarians can help navigate and guide self-directed education projects like getting a better job or learning a new skill, for example. Advocates for an education focus argue that no public institution is better positioned than libraries to fill the gaps in the formal education system. Practitioners like Valerie Gross have made a compelling case that funding for education carries the political weight of an essential service and actually serves a broader demographic. One weakness of an education focus, though, is that it requires a fairly significant shift in the role/training of librarians and a concerted effort to shift public perception.

This survey was designed to understand whether librarians generally believe that an educational focus is the way forward for their library.

Survey Results

This survey collected responses from over 500 librarians at public libraries, mostly in the US and Canada, a meaningful sample, statistically speaking. Here are the responses to each of the questions.

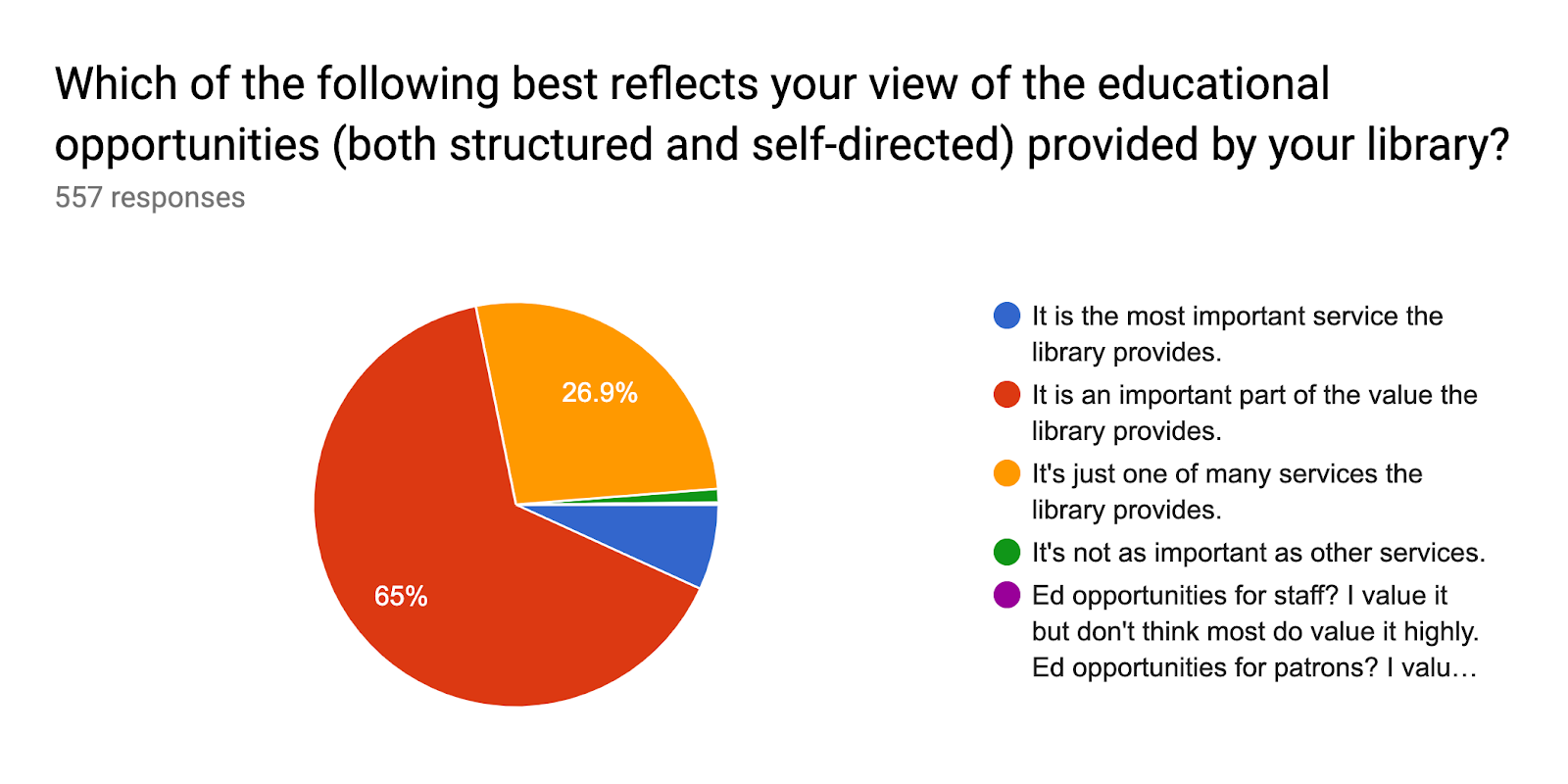

The survey indicates that very few librarians (around 7% in our sample) believe that educational opportunities are the most important service offered by their library. A strong majority (65%) feel it is important, but the percentage that feel it’s just one of many services offered by the library (almost 27%) is much larger than those who feel it’s the most important service. Clearly, the idea that libraries should be primarily educational institutions has not caught on in a meaningful way.

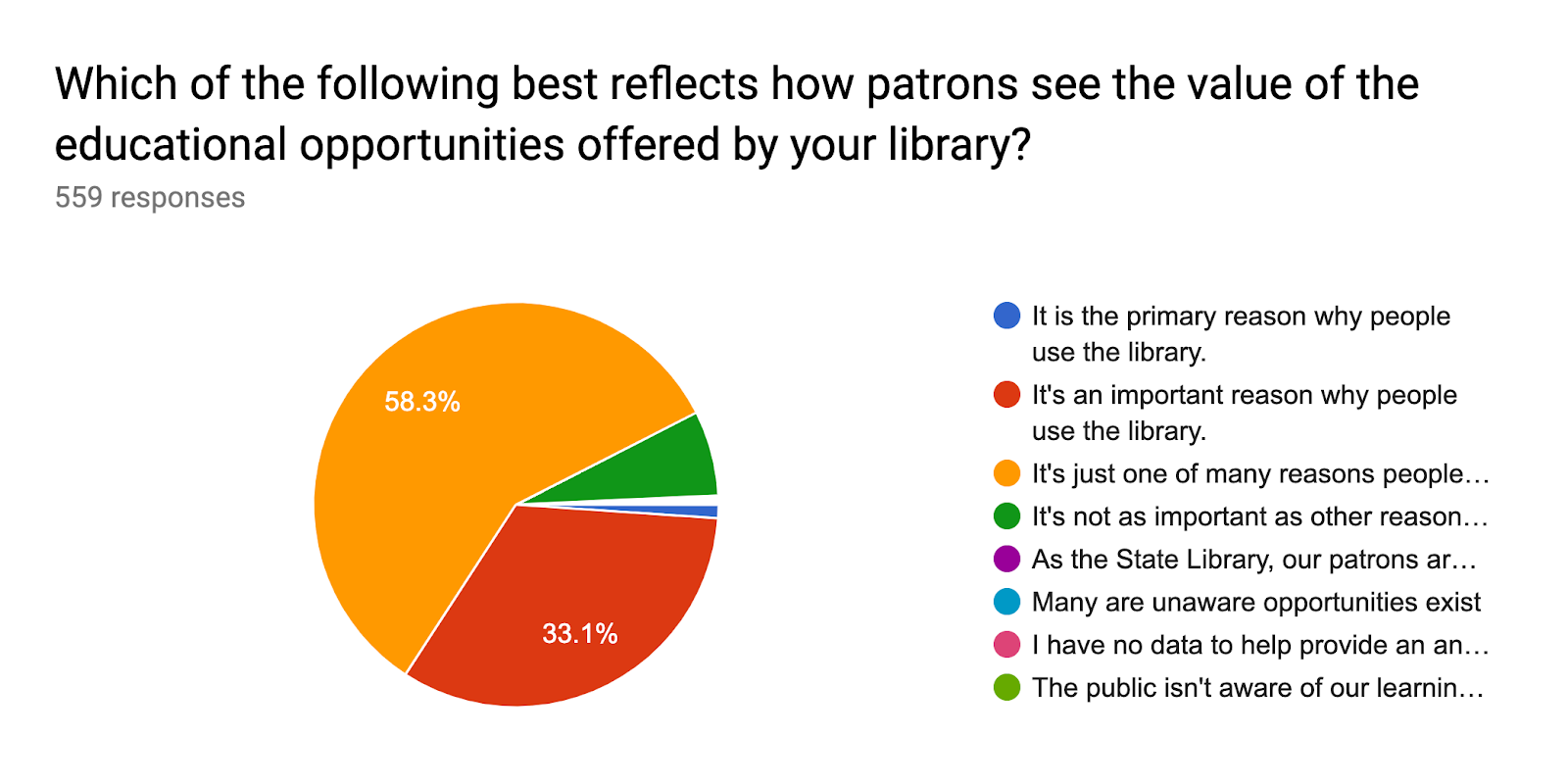

It is interesting to note that, by contrast, librarians perceive the public placing a much lower value on the library’s educational offerings than they themselves do. A solid majority (58%) report that the public sees the educational offerings as just one of many services and only a third of respondents believe it is an important reason why people use the library. Each of the responses to this question ended with the phrase “reason why people use the library”, so it seems fair to conclude that our respondents based this judgement on observed usage. The responses of those who chose the "other" option also confirm this conclusion.

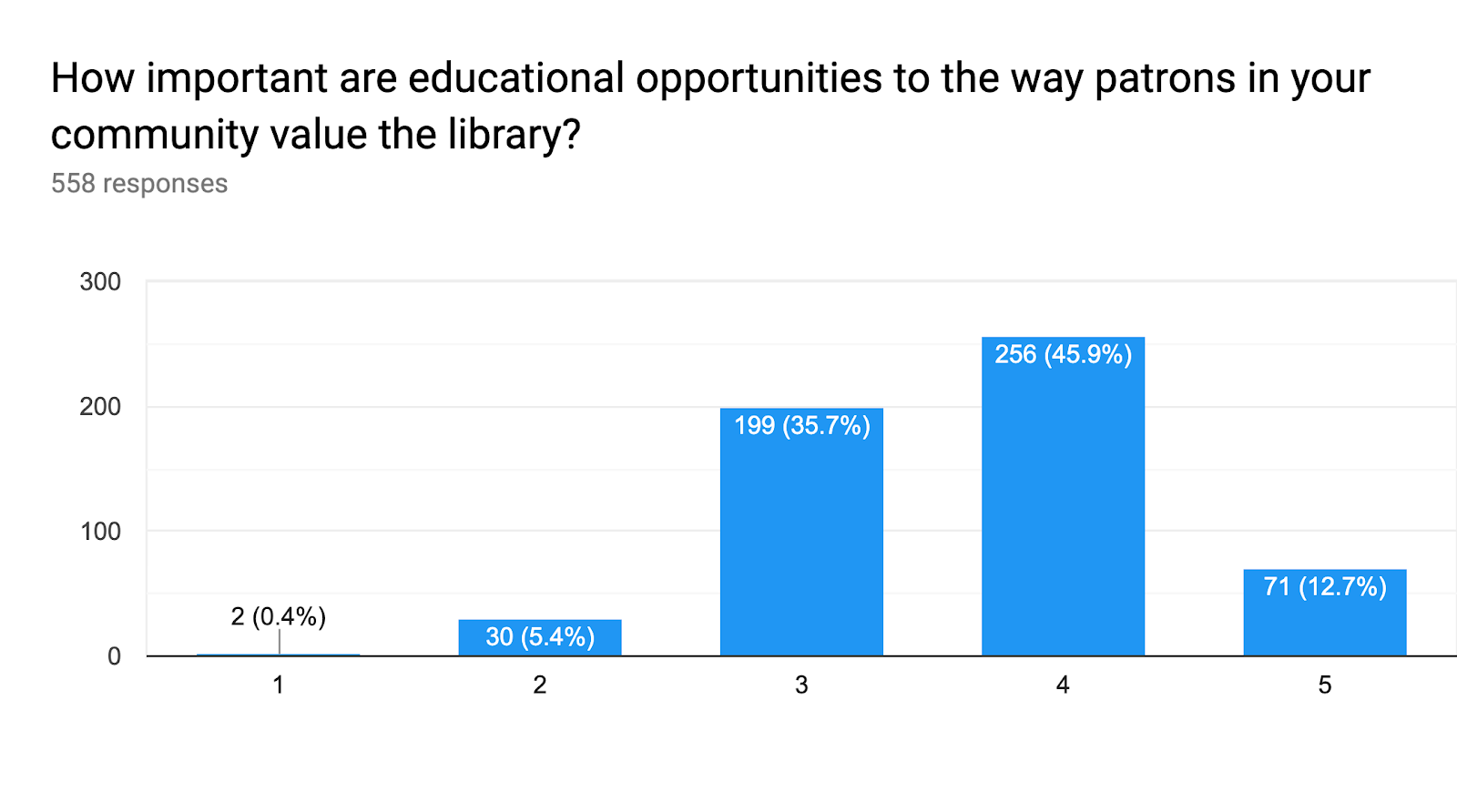

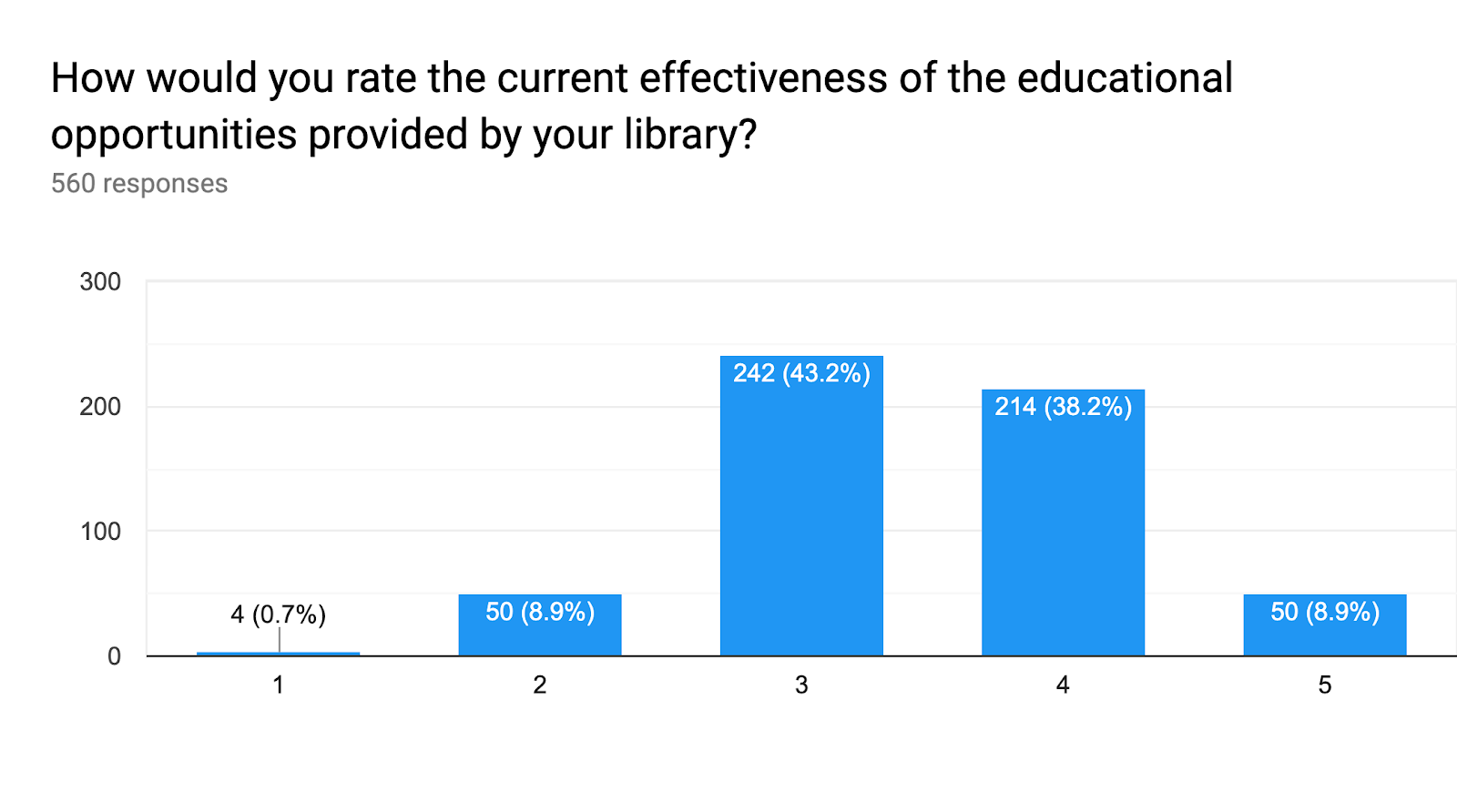

This question was intended to triangulate the question just above it. Rather than focusing on usage, this question simply offered a 1-5 scale and asked just about the value patrons place on the educational offerings at the library. This probes an observation made by a Pew study several years ago that people support libraries based on the value they believe is provided to other people, not necessarily based on their own usage. Framed this way, 13% gave educational opportunities the highest possible importance ranking, nearly twice as many as in the first question. The overall result, though, is far from a reflection of a library as primarily an educational institution. Most respondents see educational offerings as worthwhile, but not primary.

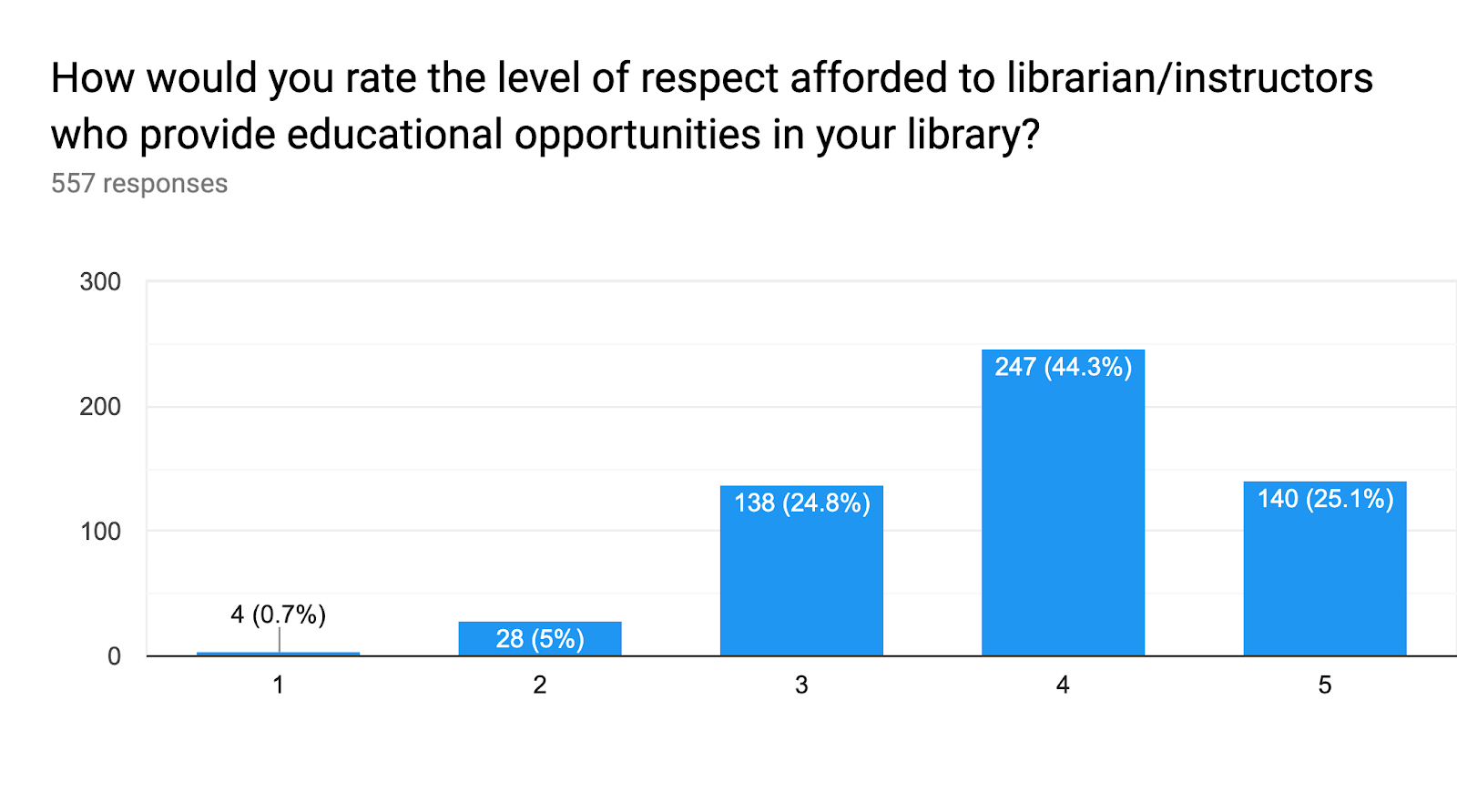

Another potential suppressant to library educational offerings would be a low perceived level of respect afforded to the librarians who provide those opportunities. Fully a quarter of respondents (25%) indicated that librarian/educators are “Highly Prized”. The largest group (44%) indicated a 4 out of 5 and less than 6% of respondents leaned toward the “Not Respected” end of the scale. It seems fair to conclude that library educational offerings are not neglected because librarian/educators are disrespected or that librarians are deflected from an education focus in favor of higher prestige career tracks.

Which of the following education opportunities does your library currently provide?

88% In person classes

76% One-on-one research or tech support

63% Information curation or research guides for topics, skills, and subjects of local interest

40% Asynchronous online classes and tutorials

10% Live online classes

The survey sought to ascertain what library educational offerings are currently most common. The results indicate a predominance of offerings that rely heavily on direct participation of a library educator as opposed to offerings that are entirely self-service or automated.

nalysis

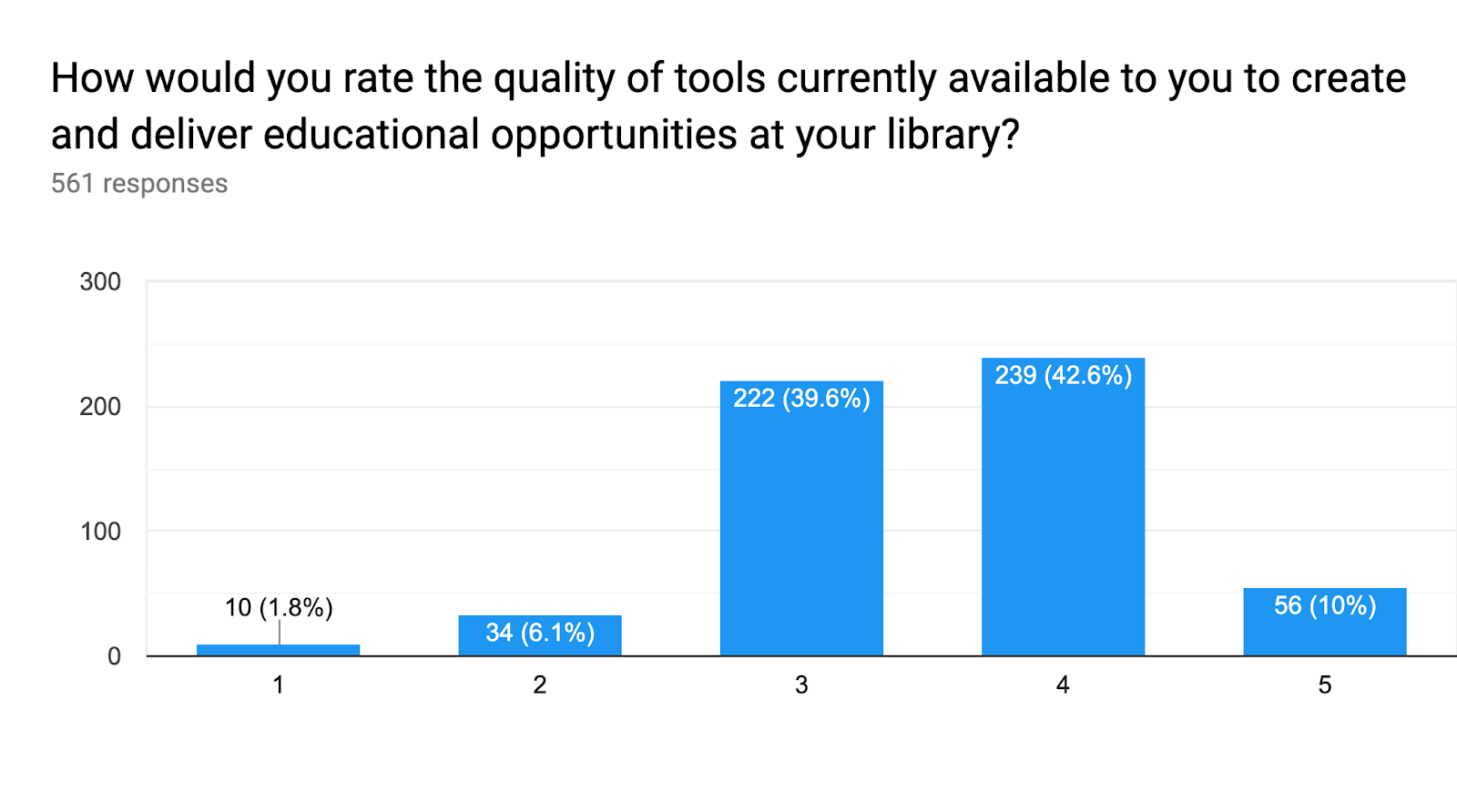

The last question in the survey probed a third possible suppressant to library educational offerings: the existence of barriers to creating and delivering educational opportunities. Here again, this does not seem to be a major issue. Less than 7% of respondents leaned towards poor tools. A solid majority, in fact, leaned toward the “Excellent” end of the scale.

Conclusions

Librarians have not, generally, bought in to the idea that libraries should be educational institutions. This lack of buy-in does not appear to be because library educational offerings are ineffective, or because librarian/educators are disrespected, or because they don’t have the means to create and deliver those offerings. Librarians generally believe that the public places value on library/educational offerings, but not enough to warrant a singular focus. Rather than focusing on an education value proposition, librarians generally appear to favor multiple value propositions.

It’s not possible to determine from these results whether libraries are responding to public or “market” demand in this regard or whether other factors are in play. Other possible factors might include, direction from decision makers outside the library, positive traction from other value propositions, or even simply institutional inertia. To make that determination, it would be helpful to explore to what degree libraries have studied market needs in a systematic way and what the experience has been over time for libraries that have attempted a serious educational focus. It's also worth remembering that this survey reflects only one point in time.

About the author: